TamTam Books News

Saturday, December 16, 2006:

There are only two great NEW albums released this year.

Sparks' "Hello Young Lovers"

I've listened to this album at least four times a week since it's release. For sure it made me a more balanced person. I have a better understanding what 'life' is and where it's going. I listen to music all the time. And this album is number one. There is not one bad song on it. In fact I am amazed at its complex arrangements, beautiful melodies, its swing, its bounce, its gall to be the best album of the 21st Century.

Yes you are thinking, "TamTam Books has totally flipped." Gone to the other side of the dark planet. But as I mentioned on this blog and elsewhere, if you have this album and you don't like it - well, I don't like you. It is simple as that. This is a great album. "Hello Young Lovers" is about life, pleasure and pain. You don't like life, pleasure and pain?

Scott Walker's "The Drift"

Unlike Sparks' "Hello Young Lovers" this is an album about history and hell. In fact this album is hysterical (so is Sparks' "Hello Young Lovers") because it is so dark that humor is bound to come out. Scott Walker is a remarkable writer and probably one of the great poets who is writing music these days. Yes Dylan has his strong points on his latest album, but he's coasting. Walker, at the same age, is pushing the music and lyrics forward and upward... or is it downward. Either way it's going for the throat. This album doesn't take no prisoners. Either bow down to its greatness or get out of the room.

I think this is a beautiful album full of beautiful stuff. In fact when I saw David Lynch outside Tower Records, I bought him this album. I think he should listen to it -and since I don't know him, he may have thrown this CD outside his car window. I doubt he would do that. Nevertheless who ever picks up this album from the street will find wonders and desires that are intense. We live in a horror show now, and art has to be really strong.

The two albums here are strong and brave. Buy them and surrender to their greatness.

Tosh // 4:07 PM

______________________

Friday, December 08, 2006:

It is interesting what is in Syd Barrett's estate at the time of his passing. For the most of the world he was a reclusive man. Here are some of items and artwork from his estate:

Tosh // 9:15 AM

______________________

Syd Barrett's paintings from his estate

Tosh // 9:10 AM

______________________

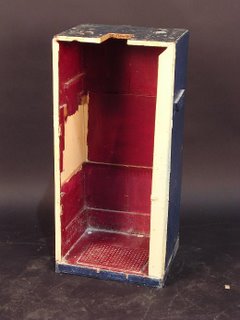

Syd Barrett's self-made funiture from his estate

Tosh // 9:02 AM

______________________

Monday, November 27, 2006:

Tosh // 7:43 AM

______________________

Monday, November 20, 2006:

"LUN*NA MENOH: 1986-2006"

Curated by Kristine McKenna

December 2nd is the opening

Exhibiton runs from December 2 to December 23, 2006

Track 16 Gallery is pleased to present the exhibition, Lun*na Menoh:

1986-2006. The exhibition will run from December 2 through December

23, 2006, with opening reception for Lun*na Menoh from 6 to 8 P.M.,

with a fashion show featuring the work of Lun*na Menoh to follow, as

well as a performance by her band, "Jean Paul Yamamoto".

This first full career survey of Los Angeles artist Lun*na Menoh will

feature multiple works from all her art-making practices––painting,

sculpture, performance art, and video. Anchoring the exhibition are a

dozen of Menoh's subversive one-of-a-kind sculptural garments. In the

Surrealist tradition, these wearable artworks are at turns witty,

diabolical, and unabashedly beautiful. "The Magical Story Teller

Dress," for instance, is a mechanized gown with a full skirt that

incorporates several picture frames; as the wearer weaves her tale,

paintings in the picture frames shift to illustrate the story. "Men's

Wardrobe" is a clothing rack of men's wear that's been stripped down

to nothing but the seams, and "Which Room Do You Want to Get Into?" is

a bright yellow jumper inset with fantasy boxes evocative of work by

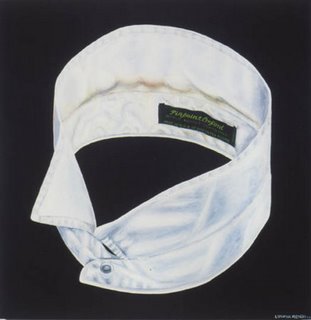

Joseph Cornell. The show will also include several pieces from Menoh's

"Dirty Shirt Collar," project, which includes a line of clothing

fashioned entirely from dirty shirt collars, and a series of painted

portraits of her favorite dirty collars. The founder and sole member

of the band Jean Paul Yamamoto, Menoh recently premiered her work of

musical theater, "A Tribute to Yoko Ono," at LACE.

www.track16.com

(for address, directions and basic information)

http://www.track16.com/exhibitions/lun-na_menoh/index.html (to view

some of Lun*na's work)

Also the catalogue "LUN*NA MENOH: 1986-2006" will be at the exhibition as well!

Tosh // 7:30 AM

______________________

Saturday, November 18, 2006:

This is a great article by the fantastic Jon Savage on the incredible Joe Meek

http://observer.guardian.co.uk/omm/story/0,,1942723,00.html

Meek by name, wild by nature

Jon Savage

Sunday November 12, 2006

Observer Music Monthly

On 12 August, 1966, the Tornados released their last ever record with Joe Meek. Beginning with the sound of waves and seagulls, 'Is That a Ship I Hear?' bore all its producer's hallmarks: the boot-stomping drums, the extraterrestrial keyboard sound, and fierce, fierce compression. Like its predecessor, 'Pop-Art Goes Mozart', it was constructed around a gimmick. Meek hoped that the title and the ocean effects would convince the DJs on the pirate stations - Radio Caroline, Radio London, Radio City et al - to put his new record on heavy rotation. Just when the pirates' influence on the British charts was at its height, it seemed like a good angle.

However, this was not the Tornados' time. On 12 August, Revolver was on its first week in the British record shops. Blonde on Blonde was issued on the same day as 'Is That a Ship I Hear?'. While the Dylan album got detailed track by track rundowns in the British music press, the Tornados got short shrift: 'a whistleable little melody of promise'; 'good of its kind and doubtless a hit three years ago, but not for today's market'. It had been a long slow fall since 'Telstar', number one in the UK for five weeks in autumn 1962: the group hadn't had a hit since late 1963 and there were none of the original members left.

Yet while 'Is That a Ship I Hear?' was a shameless attempt to ride the pirate wave, the flip was something quite different. 'Do You Come Here Often?' begins as a flouncy organ-drenched instrumental and stays that way for over two minutes. By that time, most people - had they even bothered to even turn the record over - would have switched off. Had they remained they would have heard two sibilant, obviously homosexual voices bitching, well, just like two queens will.

The scenario is the toilet in a London gay club, possibly the Apollo or Le Duce. The organist is still pumping away, but that's only background, as the sound dims and the bar atmosphere comes in.

'Do you come here often?'

'Only when the pirate ships go off air.'

'Me too.' (giggles)

'Well, I see pyjama styled shirts are in, then.'

'Well, pyjamas are OUT, as far as I'm concerned anyway.'

'Who cares?'

'Well, I know of a few people who do.'

'Yes, you would.'

'WOW! These two, coming now. What do you think?'

'Mmmmmm. Mine's all right, but I don't like the look of yours.'

(A sniffy pause)

'Well, I must be off.'

'Yes, you're not looking so good.'

'Cheerio. I'll see you down the 'Dilly.'

'Not if I see you first, you won't.'

Exeunt, to swelling organ.

This brief but diverting exchange has the ring of authenticity. Its bickering is not just beastliness but the most important component of the camping which, as English academic Richard Dyer writes, is 'the only style, language and culture that is distinctively and unambiguously gay male'. In its social mode, camp privileges a caustic wit, best expressed by the quick-fire verbal retort, partly as a form of aggression, partly as a form of self-mockery, partly as a form of self-defence. It's an insider code that completely baffles the heterosexual majority, as it's meant to. (Why are they being so horrible to each other? Because it's good sport, and good practice for when you really need it.)

Like the Negro 'dirty dozens' - the ritualised insults of the Twenties and Thirties that have become embedded in rap - the camping spotlighted on 'Do You Come Here Often?' represents a complicated response to a hostile world. Its poisoned psychological arrows can help to control and neutralise the threat of homophobic violence: many bullies are right to fear the queen's forked tongue. Camping can provide a bulwark from which the gay man can sally forth into the world at large: it freezes the typecasting of homosexuals as effeminate, internalises it, and then throws it back in the face of the straight world as a kind of revenge.

However, that long 'mmmmmm', reverberating right through the diaphragm down to the male G-spot, gets to the heart of the matter. Meek's queen bitches are briefly united by an unstable mixture of camaraderie and competitiveness. Ever hopeful, ever alert, the gay man in cruising mode is relentless in pursuit of cock: the usual social rules go right out of the window. Sex drives the gay scene, its iconography, its economy, its inner and outer life. Meek's scenario highlights that heart-stopping instant, that highwire walk between acceptance and rejection that every gay man knows: when the Adonis turns into a Troll - not just the object of your desire but your own self.

'Do You Come Here Often?' was an extraordinary achievement: the first record on a UK major label - Columbia, part of the massive EMI empire - to deliver a slice of queer life so true that you can hear its cut-and-thrust in any gay bar today. Before 1966, homosexuality had been hinted at in odd mainstream records like Donovan's 'I'll Try For the Sun' or the Kinks' 'See My Friends', indeed had saturated Meek epics like 'Johnny Remember Me', but the allusions had been veiled. They didn't offer an insider viewpoint, just a mood or a stray word that seemed to briefly open a door usually locked and barred.

Since the early Sixties, there had been a trickle of products aimed at a market that was so off- the map as to be beyond marginal. Apart from Rod McKuen's vague but signifying spoken-word albums such as In Search of Eros , all of them were on tiny, fly-by-night labels. They took two different forms. Some took the Rod McKuen path: the sad young men, fated to wander through the twilight world of the third sex, condemned, like Peter Pan, to always be on the outside looking in. Their sensitive meditations on lust and loneliness were dramatised by covers of show tunes.

While these tragic figures, in accepting their exiled status, took care to be non-specific, the period's other archetypes were far more feisty. Unlike their more sober compatriots, drag queens could not pass, and so camping was honed into a corrosive chatter that could strip paint at 10 paces. Dovetailing into the market for outrageous adult albums by the likes of Rusty Warren ( Banned in Boston! ), nitroglycerin queens like Rae Bourbon, Mr Jean Fredericks and Jose from the Black Cat offered frank meditations on queer life: 'Nobody Loves a Fairy When She's 40', 'Sailor Boy', et al. Too real and too ghettoised, none had a hope of finding any wider distribution.

There were firm reasons for this state of affairs.

Although the law that would decriminalise it was passing through Parliament during 1966, homosexuality was still illegal in the UK, as it was in the US: punishable by prison and social ostracism. However, laws do not always reflect contemporary realities, and gay people continued to conduct their illegal sexual and social lives. For older men like Joe Meek, pleasure might have been irrevocably stained by guilt but, for the upcoming generation of 20 year olds, the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 was an anachronistic irrelevance. Fuck Lily Law and her evil twin, Laura Norder.

In fact, Joe Meek was unusually privileged, if only he had been able to take some comfort from that realisation. The music industry was one of the few places where gay men could be themselves, and indulge their sexual predilections in a way that was economically viable. Forty years ago, it was far from being the respectable career option that it is today, and indeed derived much of its energy from its outcast status. This was a natural consequence of its roots in showbusiness and theatre, but even more basic was the way in which the sexual and social aesthetic of genuine innovators such as Larry Parnes alchemised the raw material of working-class adolescents into hit parade gold. From 1957 on, Parnes bossed British rock'n'roll, and transformed all his Reginalds and Ronalds into a new Olympus peopled by emotional deities-cum-archetypes like Billy Fury, Dickie Pride, Vince Eager, Georgie Fame. His sensibility, and that of many who followed him, transmuted gay lust into the erotic longing that excited the passions of the young women who pushed these idols into the charts.

Meek arrived as the period's foremost independent producer with John Leyton's summer 1961 smash, 'Johnny Remember Me', an eldritch spasm that epitomised the heightened melodrama of teenage emotions. (Meek used to speed up all his records to achieve that very effect.) It also acted as a metaphor, for those who chose to hear, for the sense of loss and disassociation that many gay men then felt. 'Telstar' confirmed his elite sta tus and, although superseded by the Beat Boom, he was able to pull out huge hits such as 'Have I the Right?' by the Honeycombs, a summer 1964 number one and an oblique comment on his own blocked right to sexual and emotional fulfilment.

This was his last chart-topper, but Meek adapted to the prevailing conditions better than most of his contemporaries. Although identified with Fifties rock'n'roll - Buddy Holly and Eddie Cochran in particular - he was too restless and forward-thinking to get totally trapped in the past. He made a stone freakbeat classic with the Syndicats' 'Crawdaddy Simone', a Brit R'n'B record so frenzied that it put the Yardbirds' rave-ups to shame. His 1966 singles with the Cryin' Shames featured the sinuously menacing garage stomper, 'Come on Back', while the overwrought vocal contortions of 'Please Stay' - Meek's last ever hit - attracted the attention of Brian Epstein.

Although he found it difficult to place many of his productions during 1966, Meek was far from being a spent force: his interest in the possibilities of sound remained vital. He also remained a player among the British music industry's gay mafia. During the brief entente cordiale that followed 'Please Stay', Meek accompanied Brian Epstein to witness Bob Dylan's June 1966 Royal Albert Hall concert from the Beatles' box. When the freezing of all 'Telstar' royalties thanks to a copyright dispute threatened to render him bankrupt later in the year, Meek was thrown a lifeline by the EMI chairman, Sir Joseph Lockwood, who offered him a job as an in-house producer.

'Do You Come Here Often?' also emerged into a more open cultural climate. The playwright Joe Orton had used camp's caustic cadences in his smash 1964 West End success Entertaining Mr Sloane : this was the key weapon in his desired 'mixture of comedy and menace'. The extremely popular BBC radio serial Round the Horne featured two flagrant queens talking in the gay argot of the time. Executed by Hugh Paddick and Kenneth Williams, Julian and Sandy's quickfire Polari - that mixture of gypsy language, cockney backward slang, and thieves' cant - slotted right into the verbal surrealism that the Goons had made the hallmark of British comedy.

At the beginning of the decade, Meek had entitled his futuristic but stillborn space concept album I Hear A New World . Music is always ahead of social institutions, and the new world that Meek had dreamt of became tangible after 1963. The Beatles' unprecedented success marked the death knell of the Fifties hegemony, and during the next few years, the agitation for social and sexual liberation gathered pace throughout the Western world: the civil rights struggle, the women's movement, the campaigns for homosexual equality in America and Britain. The long years of stasis and repression banked up the flood, and it was ready to burst.

The most obvious sign of this uprising was teen fashion's hothouse blooms, as young women went Op and young men squeezed themselves into striped hip-huggers and polka-dot shirts - topped off with Prince Valiant bangs. 1966 saw the full mainstream media recognition of Swinging London and its associated fashion, mod. Trumpeting the 'revolution in men's clothes', Life's 13 May cover showed four young men, making like Brian Jones in front of the Chicago skyline. The cutaway teal corduroy jackets, Rupert Bear check trousers and fruit boots were not standard male gear, and the copy played up the freak-ish angle: 'The Guys Go All Out To Get Gawked At'.

Mod's hint of mint was not entirely in the heads of hostile observers. Peter Burton, who ran London's Le Duce in those years, remembered the crossover between the mods and his young gay clientele: 'both groups paid the same attention to clothes; both groups looked much alike.' Not surprising really, as their clothes came from the same shops - initially Vince in Carnaby Street (whose catalogue of swim- and underwear could almost be classified as an early gay magazine) and eventually from the John Stephen shops in the same street. Both groups took the same drug - basically 'speed', alternatively known as 'purple hearts', 'blues', 'doobs' or 'uppers'.

In February 1966, the Kinks had a huge UK hit with their dissection of this Carnebetian army. They backed up the risque 'Dedicated Follower of Fashion' - 'he pulls his frilly nylon panties right up tight' - with some extraordinary costumes, like the thigh-length leather waders sported with such gusto by Dave Davies. On the flip was one of the period's definitive statements of outsider pride, 'I'm Not Like Everybody Else', to be racked up against other garage band staples like the Yardbirds 'You're a Better Man Than I' and the Who's 'Substitute'. These calls for non-conformity and the acceptance of difference were becoming more and more strident.

This urgency defined pop's cutting edge during the first half of 1966: the unforeseen complexities and demands of 1965's emblematic records were amplified, their abrasion and innovation honed to a razor-sharp point. 1966 was a hot year, crowded with clamour and noise as seven-inch singles were cut to the limits of the then available technology. Hit 45s by the Yardbirds, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, the Supremes, James Brown, the Byrds, the Who, Junior Walker, Wilson Pickett, and Bob Dylan were smart and mediated, harsh and sophisticated, monomaniacally on the one or, raga-like, right out of Western perception into the eternity of one chord.

A blistering hostility was in the air on 12 August, so much so that you could taste it. That day the Beatles faced the first concert of their third American tour, an event marred by the controversy surrounding John Lennon's comment that the group were 'more popular than Jesus'. The formerly inviolable avatars of youth were suddenly vulnerable as DJs burned Beatles' records and the Ku Klux Klan threatened.

Time magazine's 12 August cover - 'The Psychotic and Society' - featured Charles Whitman, the sniper who installed himself in the clock tower at the University of Texas and, without warning, killed 15 and wounded 31 people. The horror triggered an anguished self-examination: Whitman's 'senseless mayhem' was not an aberration but intimately linked to American society. 'Potential killers are everywhere these days,' a psychiatrist warned; 'they are driving their cars, going to church with you, working with you. And you never know it until they snap'.

Across the Atlantic, 12 August saw 'the worst crime London has known this century'. Around 3pm, three police officers stopped a suspicious looking van near Wormwood Scrubs prison, north of the mod stronghold Shepherd's Bush. All three were gunned down by the vehicle's three occupants. A 10-year-old boy saw the whole thing: 'I saw a man shoot the policemen,' he told the newspapers; 'it was horrible and I was so scared.' Cop-killing was a huge taboo, and the nation recoiled.

'Do You Come Here Often?' partook of that season of violence, as did its author. Its candid dialogue uncovered a deep seam of outcast aggression. Camp's downside is that, unless employed with a light touch and a sure understanding of the game's rules, its ritualised viciousness can reinforce the hostility of the wider society. Peter Bur ton remembered that when he was entering the gay scene in the mid-Sixties, nothing 'was more daunting as an encounter with some acid-tongued bitch whose tongue was so sharp it was likely to cut your throat. These queens, with the savage wit of the self-protective, could be truly alarming to those of us of a slower cast of mind.'

Internalised homophobia fuels the twisted expression of an outcast's low self-esteem: instead of fighting the oppressors, why not fight those nearest to hand? Donald Webster Cory's groundbreaking 1951 survey, 'The Homosexual in America', had clearly identified poor self-esteem as one of the greatest threats to gay men's mental health - infecting every aspect of life - but it was difficult, given society's attitudes, to break the cycle of prejudice and self-hatred. Despite his bravado, Meek felt his homosexuality as a deep source of shame. He was too stubborn to tell it otherwise than it was but, ultimately, 'Do You Come Here Often?' presented gay life as a nitroglycerin nightmare.

Born in April 1929, Meek was sensitive, almost clairvoyant, but highly volatile. Brought up as a girl for the first four years of his life by a mother who had hoped for a daughter, uninterested in most boyish pursuits, Joe was called a sissy and left alone by most of his peers. This difference, coupled with his hair-trigger temper, led to the start of the persecution (both real and imagined) that lasted for the rest of his life.

As soon as he could, Meek fled rural England for London, but in the late Fifties, despite his reputation as one of the best sound engineers in the capital, he remained haunted by the fact that his emotional and sexual orientation was illegal. This laid him open, as it did generations of gay men, to ridicule, arrest, imprisonment, violent attacks and - perhaps worst of all - blackmail. In November 1963, Meek was arrested for cottaging, importuning in a public toilet: the news of his conviction made the front page. His friends were amazed. Joe could have had all the young men he wanted, as they were queuing up to be recorded by him: they concluded that he actually liked the risk.

It didn't help that Meek was spooky: obsessed with other worlds, with graveyards, with spiritualism. He claimed to be in regular contact with Buddy Holly through the spirit world, while the negativity that he experienced clung to him like worn-out, not yet shed skin. Charles Blackwell - who arranged 'Johnny Remember Me' - remembered Joe as scarier than Phil Spector: 'He was a split personality. He believed he was possessed, but had another side that was very polite with a good sense of humour. He was very complicated.' Meek terrified the usually confident Andrew Loog Oldham: 'He looked like a real mean-queen teddy boy and his eyes were riveting'.

By mid-1966, Meek's mental state was worsening as his heyday receded into the past. Giving free rein to his instincts with 'Do You Come Here Often?', he gained satisfaction from exposing a reality long suppressed. But this was a small victory, a transient revenge, as the forces ranged against him gathered speed. Jekyll overtook Hyde, as his money troubles and declining fame caused him to up his pill intake and to dabble further in the occult. He was beaten up and his prized Ford Zodiac trashed. He was also threatened by gangsters who wanted to take over the Tornados' management. His paranoia was justified; his loneliness became all-consuming.

Meek's slide into the depths of decline was played out against a minatory pop climate. Disturbance had already hit the US top 10 that summer with Napoleon XIV's banshee 'They're Coming to Take Me Away' and Count Five's 'Psychotic Reaction'. During September and October, the pure punk propulsion of Love's 'Seven and Seven Is', the Yardbirds' 'Happenings Ten Years Time Ago' and the Rolling Stones' 'Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?' rode the year's white line fever right off the rails. The last was an amphetamined apocalypse, glossed thus by Andrew Loog Oldham: 'The Shadow is the uncertainty of the future. The uncertainty is whether we slide into a vast depression or universal war.' Later that autumn, David Bowie's 'The London Boys' and the Kinks' 'Big Black Smoke' delivered bleak cautionary tales of speed psychosis. Meek's own productions - the few that were actually released - had already reached new levels of pill-saturated oddity: the bizarre helter-skelter rhythm of Jason Eddy and the Centremen's 'Singing the Blues', the nuclear-winter visions of Glenda Collins's late protest, 'It's Hard to Believe It'.

Like the Marvelettes sang, the hunter gets captured by the game, and, in January 1967, Meek's game was up. While his last ever single, the Riot Squad's 'Gotta Be a First Time', was dismissed as 'a corny bit of beat', he was implicated by association with a gruesome gay crime dubbed 'the Suitcase Murder'. Although the hapless producer had nothing to do with the young victim's dismemberment, the police interest tipped him over the edge. On 2 February, he burst into a friend's house all dressed in black, claiming he was possessed. The next morning, the 18th anniversary of Buddy Holly's death, he blasted his landlady with his shotgun before eating the barrel himself.

Joe Meek's was an extreme pathology, to be sure, with its incredible highs - just listen to the aerated hysteria of John Leyton's 'Wild Wind' - and annihilating lows, but what remains shocking is just how much his suicidal impulse was shared by many gay men of his generation. In his diary for 11 March 1967, Joe Orton wrote about a conversation he had with his friend Kenneth Williams, by then a national figure in the UK for his appearances in Round the Horne and the Carry On film series. Orton found Williams 'a horrible mess' sexually: 'He mentions "guilt" a lot in conversation. "Well, of course there is always a certain amount of guilt attached to homosexuality".'

Williams talked to Orton about a friend who had been caught soliciting: 'Found in a cottage she was,' he said. 'They gave her a choice of gaol or a mental home. She chose the mental home. "Well," she said, "there's all the lovely mental cock. I'll be sucking all the nurses off. I'm sure it'll be very gay." Kenneth said this man went into the mental home and was given some kind of treatment "to stop her thinking like a queen". The man apparently was very depressed after this and committed suicide. Kenneth then spoke of all the people he'd known who killed themselves ... he told all the stories in a way which made them funny, but it was clear that he thinks about death constantly.'

By early 1967, Orton was so successful and well-regarded that he had access to the new elite. He was approached by Brian Epstein to write the screenplay of the Beatles' third movie, which he titled 'Up Against It'. His diary entry for 24 January describes meeting Paul McCartney and listening to a pre-release copy of 'Penny Lane' and 'Strawberry Fields Forever'. As the public avatar of the new, aggressive homosexuality and, in private, an enthusiastic sex hunter - one of his most memorable diary entries concerned an orgy in a public toilet in Holloway Road in north London, just down the road from Meek's studio - Orton totally rejected Williams's sexual guilt as the holdover from a bygone era.

But even he could not escape its shadow, embodied by his older partner, Kenneth Halliwell. As the playwright's star rose, the balance of their 15-year relationship tipped irreversibly. The more that Orton flaunted his promiscuity and revelled in his success, the more depressed and inhibited Halliwell became. On 9 August 1967, he murdered Orton with nine frenzied hammer blows to the head, and then swallowed 22 Nembutals. Their bodies were found side-by-side in their shared bedsit.

Eighteen days later, the body of Brian Epstein was found in the locked bedroom of his Belgravia house. The cause of death was, according to the coroner's report, 'poisoning' by Cabrital - a kind of sleeping pill. Epstein's mental state had deteriorated since August 1966, after the Beatles' stopped touring: he hadn't been able to attend their last ever show at San Francisco's Candlestick Park because his then current boyfriend, a hustler called Diz Gillespie, had robbed him of money and valuable documents. According to his attorney and close friend Nat Weiss, that accounted for 'his first major depression: that was the beginning of his loss of self-confidence.'

The deaths of Meek, Orton and Epstein occurred just at the point when the freedoms of the Sixties were institutionally recognised, in Britain at least. As well as the relaxation of the laws on abortion and divorce, the famous 1885 statute that had done for Oscar Wilde and several successive generations of gay men was finally overhauled. The Sexual Offences Act, which became law right at the end of July 1967, substantially decriminalised homosexuality: allowing for the existence of gay social and sexual relationships, it removed the threat of blackmail and enabled the first, very basic steps to be taken towards the ultimate goal of total parity.

'Hey, you've got to hide your love away,' John Lennon had sung in one of the Beatles' most poignant songs, and, for almost every adult gay man born before the mid-1940s, the strain of having to do so was psychologically disastrous. In far too many cases, the result was alcoholism, drug addiction, compulsive cruising, crippling guilt, an inability to form lasting emotional relationships - a monstrous waste of lives.

Reactions to the new law within the gay underworld were not always positive: a renewed bout of 'queer-spotting' in the media unleashed all the old venom about bestial 'buggers'. The historian Jeffrey Weeks remembered meeting men who were 'actively hostile, nervous that the new legality would ruin their cosily secret double lives'. In the same way that the gay underworld had existed despite, if not in defiance of, the law, then the long fought-for turnaround towards partial acceptance would not easily erase the decades of vitriol and prejudice. 'We'll be free,' Kenneth Halliwell had exclaimed to Joe Orton in late July, but it wasn't that simple.

Nearly four decades on, 'Do You Come Here Often?' remains sad, eerie, funny, and true: you can still hear its vivid vituperation in the gay hardcore dance records of the 21st century. By the same token, it is time-locked, a bulletin from a pivotal point in homosexual history: that moment when an oppressed minority began to claim its rightful place in society. However, that struggle was not without its sacrifices. Like Orton and Epstein, Meek would not live to see the sun, and his August 1966 single remains testament to the lethal power of the homophobia that, once rampant in Western society, is still virulent. Guilty pleasures can kill.

· 'Do You Come Here Often?' is available on Queer Noises, an anthology of gay records from 1960-78 curated by Jon Savage, out now on Trikont. A great collection of Meek's recordings, including most of the other records referred to here, is available on The Alchemist of Pop: Home Made Hits and Rarities 1959-1966 (Sanctuary UK 2xCD). An expanded version of this article originally appeared in Black Clock (California Institute of the Arts) Issue 4: Guilty Pleasures. Thanks to Steve Erickson

Hey Joe

The sixties' space cadet

Since his death, Joe Meek's reputation as a pioneer of space-age pop and an eccentric English Phil Spector has grown apace. But in the early Sixties the record industry hardly knew what to make of the man who made a series of hits from his home studio at 304 Holloway Road in north London.

Born in 1929 in the Forest of Dean, he developed an early obsession with gadgets which he nurtured while working for the Midlands Electricity Board and which found full rein when he started to make records in 1956. The best-known of these - John Leyton's 'Johnny Remember Me', the Tornados' 'Telstar' - sounded like nothing else and, far ahead of George Martin, Meek used the studio as an instrument, taking mixing desks apart, playing tapes backwards and adding washes of sci-fi inspired effects. The fact that in his studio people played guitar in the bathroom while others sang on the stairs only adds to the fun.

Scorned by the mainstream, Meek launched his own label, so becoming an indie pioneer in yet another field. Members of Meek's house bands became huge stars a decade later - Ritchie Blackmore, who played the guitar solo on Heinz's 'Just Like Eddie', went on to form Deep Purple, along with the Syndicats' Roger Glover, whose guitarist, Steve Howe, joined Yes.

Guardian Unlimited © Guardian News and Media Limited 2006

Tosh // 11:16 AM

______________________

Friday, November 17, 2006:

Last weekend the Observer Guardian had an amazing series of articles on the relationship between Pop Music and the Gay World. I have always been fascinated by this fruitful (no pun intended) relationship. So I want to reprint some of the articles on the TamTam blog - with my illustrations or images to go with it.

This was an article titled "20 Most Fabulous," and it's a commentary by a group of fascinating gay music figures commenting on what they consider gay music icons. I found this on

http://observer.guardian.co.uk/omm/story/0,,1942200,00.html

Here it goes:

1. Blues stockings

by Tom Robinson

The term 'racy' derives from the phenomenon of 'race' records (marketed to black audiences) that blossomed with the birth of the blues in the 1920s. Classically, blues songs were about misery and deprivation, but human nature meant that songs with suggestive lyrics actually sold an awful lot better. In particular there were vivid expressions of female sexuality - as Sippie Wallace sang how she was 'A Mighty Tight Woman', and Maggie Jones wondered 'Anybody Here Want to Try My Cabbage ?'

And blues singers didn't just talk the talk. The bisexual Bessie Smith enjoyed nights in buffet flats - illegal drinking parties - which (we're told) often involved gay and lesbian orgies. She sang about it too - in 'Kitchen Man' and 'Young Women's Blues'. In the code of the time, 'sissy man' or 'freak' denoted a gay man, while 'BD' (or bull-dyker) referred to a lesbian.

When Ma Rainey (the 'Mother of the Blues') was arrested for running an indecent party, it was Bessie who bailed her out - while Ma's own 'Prove it on Me Blues' asserted: 'I went out last night with a crowd of my friends/ They must've been women, 'cause I don't like no men.'

· Tom Robinson presents The Tom Robinson show, Monday & Tuesday nights, BBC 6 Music

2. Men in skirts

by George Melly

Douglas Byng was a cabaret artist in the West End before the Second World War and was famous for his impersonations of women. His songs were full of innuendo - for instance, 'I'm one of the Queens of England'(1930) - and he's regarded as a pioneer of what we call 'camp' now.

There was widespread speculation about his private life, but among his immediate circle his homosexuality was common knowledge. He was a great friend of my mother's and I admired him enormously. He was a very sophisticated comedian - he wrote all his own material - and seemed the personification of homosexual smut. He was hugely popular: he told me once that when he'd walk down Piccadilly, all the whores would shout out to him 'Hello, Dougy, how did it go tonight?'

His boyfriends were always what we call rough trade. I went to his flat in Brighton when he was getting old and ill and cross, and one of these lads was lying on the sofa. Dougy said to me: 'This is my nephew' - he always introduced them as his nephew - and he then said to his 'nephew': 'Get Mr Melly a sherry.' The boy replied: 'Get it your fucking self!' Dougy just said: 'Aren't they so rude, young people?'

He ended up broke in an old people's home for theatricals. But he had a huge influence on the gay edge of society and he paved the way for performers such as Danny La Rue and a whole generation of artists who built up a tolerance to campness, because in those days there were a lot of violent homophobes.

· George Melly is a writer and entertainer. He is performing at Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club, November 27-29

Tosh // 8:46 AM

______________________

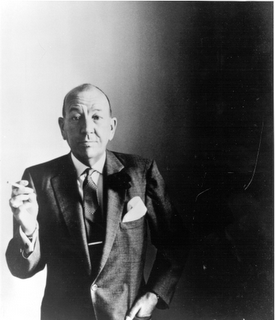

3. Will Young on the genius of Noel Coward

I find Noel Coward fascinating - particularly the notion of him as a celebrity and the extent to which that relates to our idea of celebrity now. It's almost exactly the same. He set the standard for men's style at the time - regardless of his sexuality. There's a comparison with someone like David Beckham today, who has heralded this metrosexual age. Because Coward was so suave and sophisticated and slightly effeminate, that became the way that young men wanted to present themselves. It's an astonishing level of influence for a gay man to enjoy, particularly given the fact that homosexuality was illegal at the time. And of course his relationship with fame underwent exactly that thing that every British celebrity goes through now. He was hugely popular and then hugely unpopular.

Next year I'm appearing in a production of The Vortex in Manchester. It's a play that was rather punk rock for its day, dealing with the mass consumption of cocaine - again, you can draw parallels with the present day - and then he went on to this period of unparalleled theatrical success with Hay Fever and Private Lives where he'd have three shows running concurrently in the West End at any given time. He became so nationally loved and so popular that people had nowhere to go with him but to start hating him.

I was talking about this kind of nature of success with my boyfriend only the other day. It's like what happened to David Gray. Massive. Then nowhere. But we live in a lot more fickle times now. If someone comes along and does David Gray in a better way than David Gray did it - like James Blunt did - then there is no need for David Gray any more.

What happened to Coward was the Sixties. When you have John Osborne with Look Back in Anger at the Royal Court I guess you don't really need Noel Coward. There is something essentially repressed about Coward that fell out of favour. So he went to Vegas and did shows there and bought a house in Jamaica and ... well, good on him! There is a great album called Noel Coward Live at the Sands, Las Vegas, with an iconic shot of him in the desert on the cover. I think the British saw it as a betrayal, that he was cashing in a bit on his success. But why not? England is so funny. In a way it was a double betrayal. It betrayed him so he betrayed it. And then he came back later and did a show at the Cafe de Paris with Marlene Dietrich, which must just have been the most amazing thing.

He knew everyone, of course. There are diary entries about him going to Chequers to visit Churchill and he was completely accepted by royalty and by politicians, people who were the society figures of the day. Politics and royalty were so much more glamorous then. There is a brilliant story of him taking tea at the Ritz during the Blitz. Bombs were going off around him and he said: 'How marvellous that the band kept playing.'

He does get a lot of criticism for not being more open about his sexuality, but it's all there. You could argue that he was bottling it by not being a bit more expressive, could have embraced it a little more - but you have to remember the times. And in a way his gayness did work against his classic English gentlemanliness.

The theatre and the music business were havens for people like Coward. It was one of the only places that you could have any sense of freedom about your sexuality, which follows through in the British arts right up until recently. And then you can trace it back to Oscar Wilde, who was vilified in something like the way George Michael is now. I'm sure Wilde would have been falling asleep at the wheel of his Mercedes if he was around now!

Coward's music is so important too. Largely, it is very patriotic, like 'Mad Dogs and Englishmen'. 'London Pride' is ever so ironic, if you think about it.

One of my favourite songs is 'Don't Let's Be Beastly to the Germans'. Just the title. It is so camp. But isn't that fantastic? Songs like that, and 'Don't Put Your Daughter on the Stage, Mrs Worthington' are incredibly camp. But then the British do have a very long and enduring relationship with the idea of camp. They love it. And the reciprocal situation here is that entertainment becomes a safe house for camp people. They are incubated by it. The British have a huge tradition of comedians, singers, actors, performers and pop stars who are incredibly camp, whether they are Noel Coward or Freddie Mercury. And they are all loved for it. I guess in some ways Coward didn't need to come out.

A lot of this helps to explain why I became a performer. I remember at school feeling this sense of difference, of otherness, that I think most gay people feel. You spend a lot more time observing things than necessarily participating in them and I think it gives you an eye for human behaviour that lends itself towards performance or some sort of social commentary, which Coward was fantastic at.

There's a great line from Coward's diaries: 'All I ever had was the talent to amuse.' I think that just about sums up the entire position of the gay relationship with entertainment. It is, quite literally, 'let's put on a show!' It's such a fantastic, resilient approach. Which is why I think, yes, being gay does still affect music.

· Will Young is appearing in The Vortex at the Royal Exchange, Manchester, from 17 January

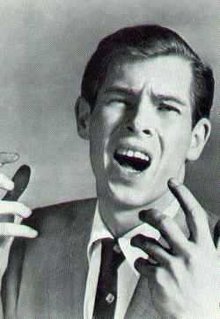

4. The crooner

by Marc Almond

When Johnnie Ray sang 'Cry' for the first time in 1951, his eyes closed tight, melodramatically falling to his knees, pounding on the piano and shedding tears, I wasn't yet born. Yet when I saw him for the first time in black and white in those lavender times, I recognised something that I felt in myself, igniting something as yet undefined to me. It was a secret I kept to myself.

The spirit of his highly emotive crooning permeated the times, paved the way for Joe Meek and his adored Heinz, for Larry Parnes (perhaps the man who really invented gay pop) and his stable of pretty proteges.

He influenced Elvis, and annoyed Sinatra. He broke down musical barriers and, particularly towards the end, became Judy in a suit - fate even brought them together in the spring of 1969 when he briefly toured with Garland. But for me, it was his handsomeness, his wide smile, the floppy Brylcreemed quiff and haunting voice that proved so heartbreaking.

Like all the great (gay) stars who found fame in less enlightened times, he exuded mystery, his sexuality blurred by marriage and 'bearded' denials. Even before his first record was released he had been arrested for importuning. In 1959, he was arrested on a charge of soliciting an undercover police officer: his career never recovered.

In performance, he theatrically caressed the microphone. He was immaculate yet dishevelled, bothered, edgy and uncomfortable as he drank and pill-popped his way to musical immortality, to the accolade of affection.

· Marc Almond's next album, Dining with Panthers, is due out in 2008

Tosh // 8:43 AM

______________________

5. The Beatles

Simon Napier-Bell on how the Fab Five changed everything

Lemar, a British act, sings serious soul. As a result, he's said to sound American. The Scissor Sisters, an American act, are outrageously camp. So everyone thinks they're British.

There's no doubt about it - just as American pop music is permeated through and through with black culture, so British pop music is permeated with gay culture. In Britain, the selling of pop was never only about catchy songs; it was about artifice and sexuality, which as often as not meant gay sexuality.

Ever since the Beatles, the imagery needed to make pop and rock stars click with the public has included aspects of gay culture. The more the public has seen of it, the more indifferent they have become to it. Robbie Williams will probably be the last pop star able to tease us with the 'is-he-or-isn't-he?' theme, his provocation silenced by Will Young's brilliance at persuading us that 'gay is normal'.

Forty years ago that was the Beatles' message too. John, Paul, George and Ringo - the most visible, most photographed, most talked-about four people the world had ever known - had a gay manager. And they took him everywhere with them.

Brian Epstein was known as the fifth Beatle. Travelling with his group, Epstein was seen endlessly on TV and in the papers, meeting world leaders and celebrities. Though London was swinging, being gay was still against the law. But with someone gay in such a super-privileged position, it just didn't seem to matter. The Beatles' popularity, coupled with their affection for their manager, made it a sure bet that Harold Wilson's government would move forward on legalising homosexuality. Unintentionally, the Beatles were helping force the issue.

But there was more to it than that. Beatles music was played at every gay party, every gay disco, every gay bar and pub. While teenagers dreamed of being John, Paul, George or Ringo, business-minded gays saw another option - be a pop manager like Brian Epstein.

It worked. By 1966 the music business had become more gay than straight. The Beatles, the Yardbirds, and the Who had openly gay managers while the Rolling Stones had one who seemed to swing both ways. The backstage area of pop had become a haven for gays - songwriters, record producers, stylists and TV directors - but especially managers. Robert Stigwood managed the Bee Gees. Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley managed Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich. Vic Billings managed Dusty Springfield.

The artists, though, were mainly not gay. Which is exactly what made it work so well. Straight kids who teamed up with gay managers found themselves liberated from their dull upbringing. Encouraged to be outrageous, they threw themselves into it with abandon. When Mick Jagger got himself arrested for pissing against a wall; when Rolls Royces were driven into swimming pools and hotel rooms smashed, you could be sure it was done with a wink and a nod from the manager. It was largely this subversive gay input into Sixties pop that converted it into the rock music that invaded American stadiums in the Seventies.

With glam rock, the influence of all this backstage gay banter began to show itself front of stage too. Among the new batch of stars were some who were gay and many who were 'bi', but apart from Bowie, most were too cautious to cross the line from visibly camp to actually homosexual. It was only in the Eighties that gay artists started rejecting the ambivalence that had been the operating norm for previous generations. Even so, while projecting themselves as totally gay they still dodged the subject of bedroom proclivities. It's difficult to believe now, but in the Eighties Boy George and Marc Almond managed to keep the straight public guessing about their sexuality. It wasn't so much about hiding it as keeping it under an alluring veil.

Now even that has been pushed aside. Will Young presents his homosexuality with no compromise and it matters very little. The accepted wisdom of the music business was that female fans would be turned off by a male star who was gay. Yet since screaming for sex with your pop idol is likely to be a hopeless fantasy anyway, it seems to make little difference.

But what would have happened 40 years ago if one of the Beatles had turned out to be gay? Or even just a tiny bit 'bi'? In 1983, when my book You Don't Have to Say You Love Me was first published, I received death threats from outraged Lennon fans for suggesting that he and Epstein once shared a kiss. By the time the book was republished in the Nineties this had been more than confirmed by several biographies (in fact, Lennon and Epstein had tried an experimental dirty weekend together in Spain), but no one seemed to care any more.

In the Sixties a tabloid report like that would have been the death of the Beatles. Nowadays it does little more than raise eyebrows.

What a wonderful change!

· Simon Napier-Bell is an author and was the manager of, among others, the Yardbirds, Wham! and Japan

6. The soul diva

David McAlmont pays homage to 'Queen Beehive'

When Queen Victoria's government tried to legislate against lesbianism, the Queen thought the idea ridiculous as she didn't believe such a thing could possibly exist. It seems that Dusty Springfield was one of these non-existents. She won four NME awards during her own Sixties reign, and her sexuality was obvious to the gay crowd. I don't know that it matters in the face of such awesome music but for those who believed that she might be, those who thought it obvious or those who were similarly inclined, it must have meant the earth when she let her sexuality slip to Evening Standard journalist Ray Connolly in 1970 ('A lot of people say I'm bent, and I've heard it so many times that I've almost learned to accept it,' she said. 'I know I'm perfectly as capable of being swayed by a girl as by a boy').

Personally, I love the album Dusty in Memphis - for its sexual frankness, the production values and the affected coquettishness of Dusty's vocal performances. I also love 'You Don't Own Me' and 'You Don't Have to Say You Love Me'. Once heard never forgotten.

Nonetheless, my unassailable favourite song is ' What Have I Done to Deserve This?', which she recorded with the Pet Shop Boys in 1987. I remember exactly where I was, what time of day it was and what I was wearing the first time I heard it: WHSmith in the Whitgift Centre in Croydon, buying a copy of Smash Hits. I still experience a palpable thrill whenever I hear the intro with those stabs of stately, classy brass, ushering in Neil Tennant's laconic, pop-on-a-smoking-jacket drawl. He then steps aside for Queen Beehive to produce a profound interpretation of Allee Willis's sugary chorus. The song reached number two in the charts in Britain and America and while Dusty owned the Sixties, here she was with us again before we finally lost her. I salute the Pet Shop Boys for remembering how much we all loved Dusty when so many of us had forgotten.

· David McAlmont is part of McAlmont and Butler with Bernard Butler. Their most recent release is the single 'Speed'

Tosh // 8:40 AM

______________________

7. 'The seventies was a fantasy age - he was the ultimate fantasy figure'

Boy George on his first sighting of David Bowie

The beginning for me was seeing David Bowie on the Old Grey Whistle Test singing 'Starman' in February 1972. I was 10. Of course, then I saw the Ziggy Stardust tour at the Lewisham Odeon in 1973 - the tour that ended with the last ever Ziggy concert. It was such a nightmare to get tickets for. My grandmother was staying with us and my gran and my dad were always at each other's throats. They were locked in constant battle. My nan stopped me from trying to get tickets- 'what do you want to go and see that poof for?' - but because my dad wanted to upset my nan he got me one. I lived in Eltham and I only had the bus fare to get one way to Lewisham so I had to bunk my fare on the way back.

I knew I was gay by that time - I hadn't had my first sexual experience, but it came not long after. Discovering Bowie and those first experiences totally connected. Just seeing this whole other world was enough to spark my interest.

I got my auntie Jan to give me a Ziggy haircut for the night, but it was a bit feeble. It looked more like [Slade's] Dave Hill. I had a cheesecloth shirt that I'd borrowed off my brother and an embroidered jacket - a bit hippyish - and I remember getting to the gig and thinking I looked really sappy compared to all these other fantastic people.

Later, aged about 17, I was working as a messenger for a print firm in Hanover Square. I used to dress up and wear make-up - a bit punky. A very handsome, older, Italian man approached me one day. He said: 'Are you a girl?' and I said: 'No' and he said: 'Well, what are you?'. 'What do you mean, what am I?' I said. 'Well, I'm a boy.' And he said: 'Have you got a girlfriend?' and I said: 'No' and he asked if he could come with me. I said: 'I'm working!' but he followed me anyway and the next thing was, he invited me to a party.

I went with him to somewhere in Queensway [west London] and the first person I saw at the party was the dancer and choreographer Lindsay Kemp, who I knew all about through Bowie because he'd influenced him hugely. The party was at a house that belonged to Anton Dolin, the great ballet dancer. It was all very snobby, but as soon as I saw Kemp I went over to speak to him and he took my hand, brought it up to his lips, and kissed every one of my fingers. I said: 'Thank you' and he said: 'Ah, but the pleasure is all mine.' It's something that has never left me! And it was thanks to Bowie that that happened.

Rock'n'roll in its truest form is a fantasy realm where you can be whoever you want to be. It has no connection with the real world. Recently, there's been all this obsession with 'reality' and I think it's dragged music down with it to make it a lowest common denominator thing. But generally, certainly in the Seventies, music was fantasy - and Bowie was a fantasy figure. Bowie in Sainsbury's just was not going to happen. You imagined him living off space-age food. He never got up in the morning to find he had ran out of milk. I used to think that he'd just sit around and be visited by other people from the rock world. Maybe someone from the Sweet would pop round with some cakes. It was this idea of a fantastic bohemian lifestyle that you wanted to engage with.

I thought it was very brave of him to say he was bisexual. I don't actually think it matters whether he was telling the truth or not. Straight people have always made better homosexual pop stars. Certainly Bowie gave me the green light to start exploring my own sexuality.

· Boy George and Amanda Ghost's new single, 'Time Machine', is out on 13 November on Plan A

8. 'Glad to be gay articulated the desire for queer freedom'

Peter Tatchell on Tom Robinson's anthem

Released in 1978, when homophobic persecution was actively promoted by church and state, 'Glad to be Gay' was the world's first explicit gay pride pop song, sung by Tom Robinson, the world's first out and political gay pop star. Almost instantly, it became the de facto queer national anthem.

The song hit me emotionally. It damned homophobia and articulated the cry for queer freedom. It was the musical equivalent of the Gay Liberation Front Manifesto - uplifting and empowering.

Tom's lyrics savaged the bigotry of the police, church, judges and media. He also had the courage to take a dig at the internalised homophobia of self-hating, closeted queers - the enemy within. That was daring and ground-breaking too.

The repressive reaction to 'Glad to be Gay' helped highlight the homophobia Tom was singing against. His record company, EMI, was nervous about releasing a queer song as a single [it came out on the 'Rising Free' EP]. Many radio stations refused to play it. Gay was obscene, according to the BBC.

Homophobia has ebbed since 1978 and 'Glad to be Gay' helped make that possible. Thank you, Mr Robinson.

· Peter Tatchell is a human rights campaigner

Tosh // 8:36 AM

______________________

9. The glam god

Morrissey on the first major label gay star

I bought the first Jobriath album in 1974 at Rare Records in drizzle-fizzled Manchester. Neither for the ears of the elderly nor for those with middle-aged perspectives, Jobriath voiced the excess destitution of New York's most tormentedly aware, whose lives were favoured by darkness. Cinematic themes of desperate dramas in paranoid shadows were presented as choppy and carnivalesque melodies.

The hairy beasts who wrote for the music press laughed Jobriath off the face of the planet. He was, at best, merely considered to be 'insane'. It was clear that Jobriath was willing to go the gay distance, something that even the intelligentsia didn't much care for. Elton John knew this in 1973; Jobriath didn't. Surrounded on all sides by Journey, Styx, and Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Jobriath was at society's mercy. Yet it could have worked so well.

Neither America nor England was quite ready. Thus, Jobriath quietly expired, buried without a single line of ceremony in any music publication throughout the world.

· Morrissey tours the UK in December

10. Girl about town

Erica Roberts considers Polly Perkins's charms

Sporting collar, tie and pinstriped suits designed by John Stephen, Sixties and Seventies lesbian singer-cum-thespian Polly Perkins cut a dashingly gender-bending figure, and was frequently photographed smoking fat cigars. Aged just 15, she was the youngest performer to appear nude at the Windmill, and never hid the fact that she was a lady-lover - rare for any entertainer of the time.

Raised in a theatrical family, Polly sprinkled her speech with Polari and, although hit records eluded her, she racked up newspaper column inches because of her camp stunts. During her spell as the first compere on cult TV show Ready, Steady Go, Polly paid a young male 'ex-lover' to fling himself at her.

She became a much-loved figure in Soho clubs for her smoky rendition of Edith Piaf's 'Je Ne Regrette Rien' and her self-penned lesbian anthem 'Superdyke'. In 1973, Decca released her album Liberated Woman. She now lives in relative obscurity in Spain with her girlfriend and her youngest son Timmy.

· Erica Roberts is a writer for DIVA magazine

Guardian Unlimited © Guardian News and Media Limited 2006

Tosh // 8:26 AM

______________________

Sunday, November 05, 2006:

Andy Warhol's "Tarzan and Jane Regained . . . Sort Of "

Wallace Berman's "Aleph"

With respect to my father's exhibition (Semina Culture: Wallace Berman and his Circle) that is taking place at the Berkeley Museum, there will be some cool films along with the show. My father's film "Aleph" will be shown as well as the rare Andy Warhol film starring the great Taylor Mead as well as my father and yours truly playing "Boy." I know.... Don't ask!

TUESDAY NOVEMBER 21

7:30 Beat Films

Hailed in its time as a harbinger of a new film movement that prized spontaneity and lived experience, Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie's Pull My Daisy (1959) is perhaps the ultimate Beat film, narrated by Jack Kerouac and featuring Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and Peter Orlovsky. Plus: Aleph (Wallace Berman, 1956-66); Breakaway (Bruce Conner, 1966); The End (Christopher Maclaine, 1953); A Movie (Bruce Conner, 1958).

SUNDAY DECEMBER 3

2:00 Tarzan and Jane Regained . . . Sort Of

Andy Warhol (1963)

Wallace Berman, Taylor Mead, Claes Oldenburg, and other art stars appear in an Andy Warhol romp through 1963 L.A., including Berman's backyard. With Lawrence Jordan's Triptych in Four Parts (1958), featuring Berman, Michael McClure and John Reed.

PFA Theater: 2575 Bancroft Way at Bowditch, Berkeley, CA

Info: (510) 642-1124 Advance Tickets: (510) 642-5249

Tosh // 8:14 AM

______________________